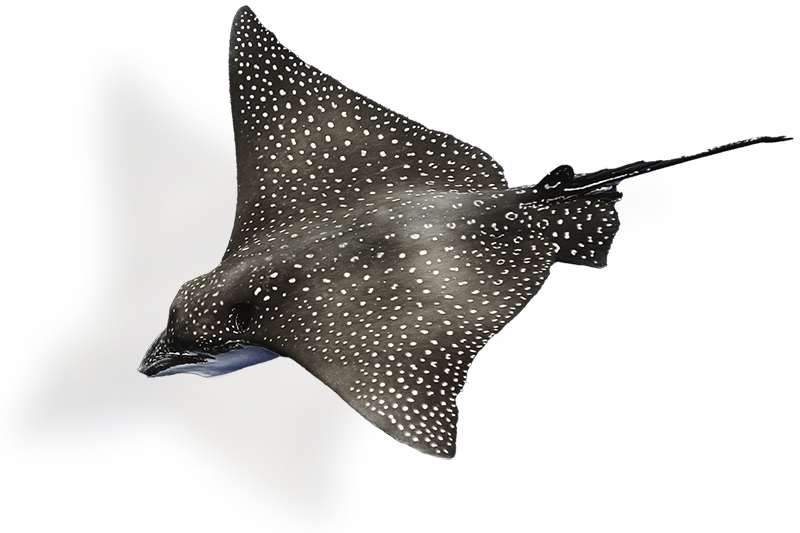

This year, the Seattle Aquarium welcomed beautiful sharks and rays to the warm waters of our Ocean Pavilion expansion. These animals came from other accredited zoos and aquariums or were diverted from the commercial fish trade. But in the ocean, large fishes like these are disappearing, mainly due to human activity.

Sharks and rays, along with deepwater chimaeras, are part of a class of fishes known as Chondrichthyes. Though they have lived on Earth for hundreds of millions of years, today about one-third of these species face extinction.

But marine scientists will not let these important fishes sink quietly into oblivion.

A team of researchers, including the Seattle Aquarium’s species recovery program manager Riley Pollom, spent years studying patterns of their decline and developing an aquatic Red List Index to study the threat of their extinction.

“Sharks and rays are one of the oldest evolutionary lineages on the planet. They’re part of our global heritage. And if we lose any of those species, we’re losing millions of years of evolutionary adaptation.”

—Riley Pollom, species recovery program manager, Seattle Aquarium

Sinking population numbers

The study comes at a crucial time. Since 1970, Chondrichthyan populations have decreased by over 50%, according to the team’s analysis, which was published in the journal Science last month. Sharks and rays are threatened primarily by overfishing, being targeted or accidently caught as bycatch. Other threats include pollution, habitat loss and climate change.

Declines in shark and ray populations tend to begin close to land—like in rivers, estuaries and coastal waters—before spreading outward, to the upper part of the open ocean and finally to the deep sea.

This worrying trend spells trouble for their ecosystems. These large fishes play important roles in their habitats, including predation, foraging and moving nutrients around different parts of the ocean. Without them, food webs can break down and the effects ripple through the ecosystem.

Lending a hand to our finned friends

Tools like the Red List Index can help governments and other organizations track population losses and determine whether their policies and actions are making meaningful strides for conservation and population recovery.

Governments can help species recover by creating and enforcing sustainable fisheries management measures. Fisheries management refers to setting, enforcing and monitoring strict limits on how many animals can be caught, where and when they can be caught, and other important rules. Some countries have seen progress in species recovery, but more work remains to be done.

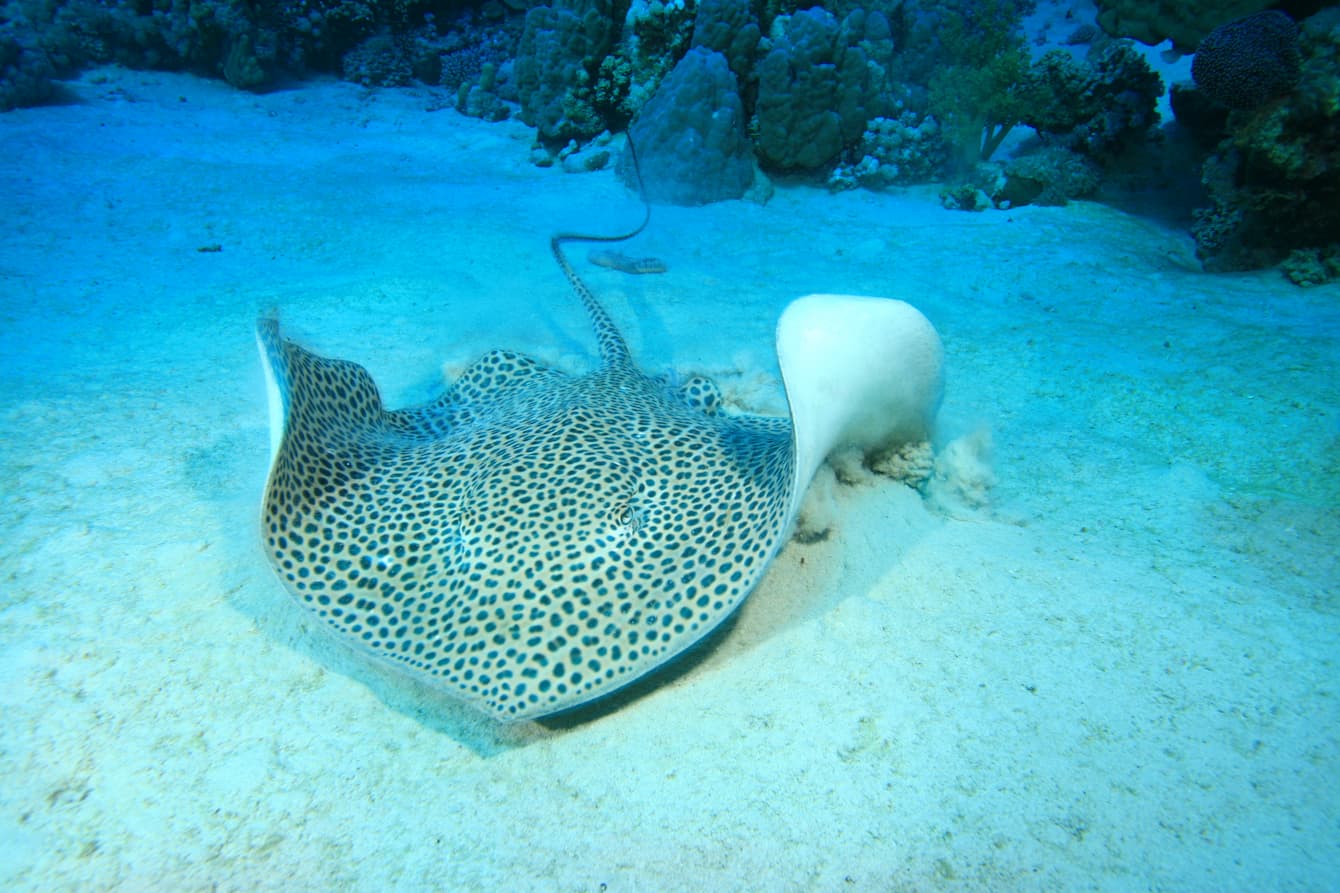

“A first step for species recovery is fisheries management. But there are some species, like Indo-Pacific leopard sharks, that are so depleted that they need an extra helping hand to replenish their wild populations.”

—Riley Pollom, species recovery program manager, Seattle Aquarium

One method of helping populations recover is by directly introducing more sharks to their wild home waters. That’s the idea behind ReShark, a global coalition—of which the Seattle Aquarium is a founding member—that works to restore wild shark populations, starting with the Indo-Pacific leopard shark.

Accredited aquariums help sharks already in human care reproduce, and transport the eggs to nurseries in the Indo-Pacific. Once hatched, the sharks are reared, tagged and released into marine protected areas, where fisheries are effectively restricted. Right now, the Seattle Aquarium serves as the North American hub for these egg transports. Once fully mature, the Indo-Pacific leopard shark in our care will help directly contribute eggs to this effort.

We can do our part by voting for politicians who support marine-friendly practices and pressuring those in office to do more to help the ocean and its inhabitants. Choosing sustainable seafood is also a great way to protect sharks, rays and other fishes. The Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch is a helpful guide for making ocean-friendly dining choices.