“When people really care about these creatures and the ecosystem, things will change in a positive way.”

―Dr. Zhenyu Tian

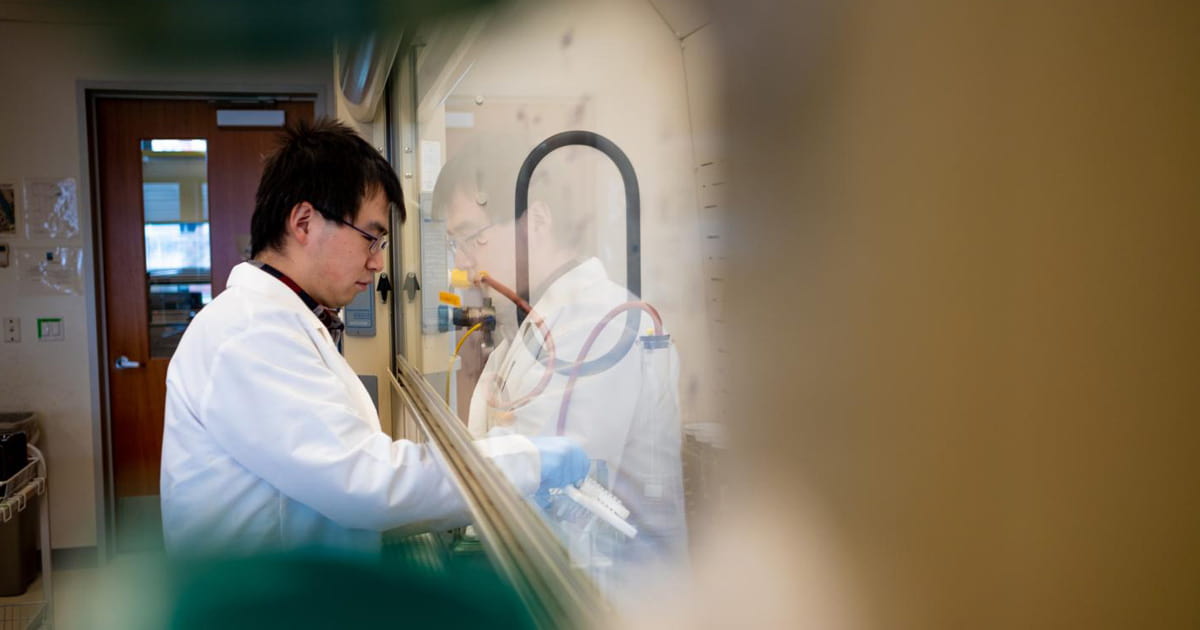

Dr. Zhenyu Tian is an environmental chemist curious about organic pollutants in the environment. He received his Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina, where he studied the transformation products and co-occurring pollutants of PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) in contaminated soil. Then he worked as a postdoctoral research scientist at the Center for Urban Waters, University of Washington Tacoma, applying non-target screening to identify emerging contaminants in water and biota and to evaluate engineered treatment systems.

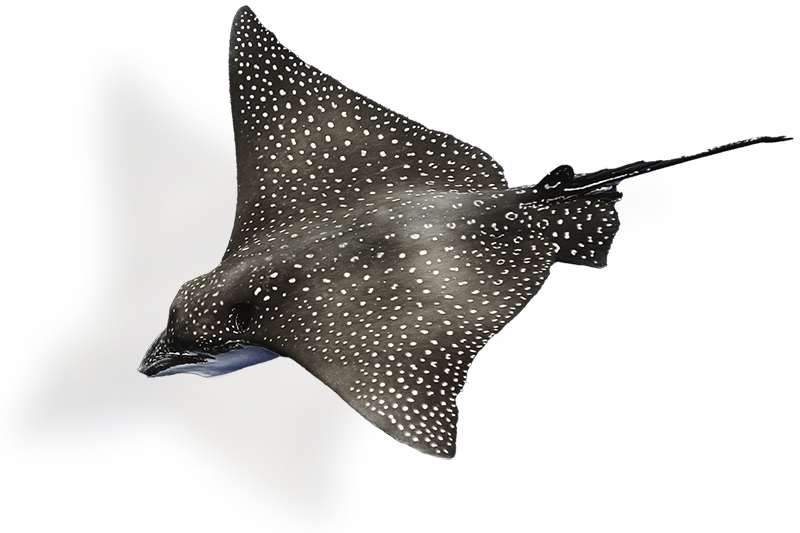

After years of collaborative research with a group of more than 20 researchers, he identified 6PPD-quinone, a ubiquitous tire rubber chemical that kills 40−90% of coho salmon when the chemical washes into urban stormwater.

It’s our honor to recognize Dr. Tian with this year’s Seattle Aquarium Conservation Research award, together with the full research group on the 2020 paper. Although we can’t gather in person for our annual Ocean Conservation Honors event, he’s kindly shared some of his thoughts with us in this Q&A.

Q: What drew you to your career?

A: Curiosity and awareness, mostly. I’m always curious about the hanging questions in archaeology and paleontology (and environmental science, of course). The curiosity is the main reason of becoming a scientist. Growing up in Beijing, I knew the concept of pollution at an early age. The city is known for its sandstorms and haze, and those and the air pollution behind them were just part of my life. So, I know environmental science is the discipline to understand the pollution issue and find solutions.

Q: What inspired you to research the deaths of coho salmon in the Puget Sound area?

A: In 2017 I was attending an American Chemical Society meeting. My postdoc advisor, Ed Kolodziej, presented a video of a coho dying from stormwater exposure. It was the first time I’d seen it. That’s when I realized it wasn’t normal, and I needed to figure out why it was happening. In later years, I saw this mortality phenomena many times in the field, and I felt the same every time. It’s a painful way of dying. And it shouldn’t be happening.

Q: What keeps you doing the work that you do?

A: Partly curiosity, as I described above. And a feeling of responsibility. Sometimes I feel like environmental chemists are like sentinels and detectives. We’re responsible for watching out for the potential threat to the ecosystem and the humans. And if something bad is going on (like the salmon mortality), we should find out why. Such responsibility is part of my motivation.

Q: What impact do you hope to make with your work—what legacy would you like to leave?

A: Maybe it’s too early to talk about legacy, but I hope our work in environmental chemistry can inform the government, industries and the public about the issue of chemical contamination. As an industrialized society, we’ll keep producing and using chemicals, but more careful examination and regulation should be considered. I hope our research could help the regulatory agencies with their decision making and help the industries to improve their formulation.

Besides, I hope our work can inspire a new generation of scientists. We have interesting and important questions in the field of environmental sciences.

Q: Ocean conservation is essential for the future of our marine environment. What does conservation mean to you?

A: I’m still very excited when I see sea mammals like seals and whales in real life. So, to me, ocean conservation is an essential effort to protect these amazing creatures and the ecosystem they rely on. And I hope my work will contribute to this effort.

Q: What brings you hope for the future of conservation?

A: I see the motivation and passion of people here in the Pacific Northwest. We have very passionate citizen scientists and volunteers (e.g., Miller-Walker community in Burien) monitoring the salmon every fall, and reporting mortality cases to us. And many young people are among them. This is the hope, because when people really care about these creatures and the ecosystem, things will change in a positive way.

Are you interested in learning more about our annual Ocean Conservation Honors awards? Read our recent blog post—and read our blog post devoted to Dr. Lisa Graumlich, this year’s Sylvia Earle Medal winner.

THANK YOU TO OUR 2022 CORPORATE PARTNERS

EXCELLENCE PARTNER