In January, years of planning culminated in a hopeful moment on a beach in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. That moment centered on two baby sharks: Charlie and Kathlyn.

First Charlie, and next Kathlyn, were gently cradled in the water by marine scientist Nesha Ichida of Thrive Conservation.

A Seattle Aquarium team, Indonesian government officials, Kawe tribal community members and other conservationists watched closely. Photographers Jennifer Hayes and David Doubilet were nearby to capture the moment for National Geographic.

Nesha grasped each shark in her hands for the final time. Then she let go.

“I’m happy. And excited. And hopeful.”

Dr. Erin Meyer, Seattle Aquarium chief conservation officer in National Geographic

Charlie and Kathlyn are beacons of hope. As Indo-Pacific leopard sharks (Stegostoma tigrinum and also called zebra sharks), they belong to an endangered species. Due to commercial overfishing, these sharks have nearly disappeared from their home waters in the Coral Triangle. And despite a series of protective measures added in recent years, their numbers haven’t come back.

Hatching an ambitious plan

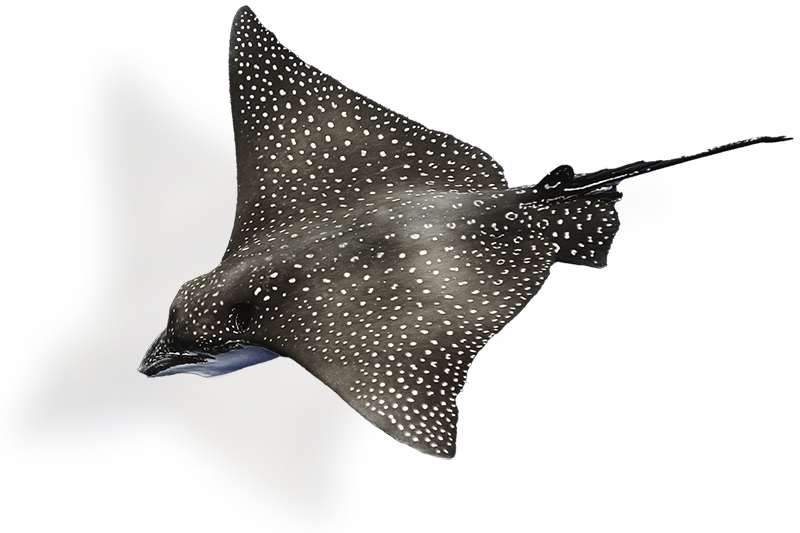

Sadly, our ocean is losing sharks and rays at an astonishing speed: More than 37 percent of species are at risk of extinction.

We and our global ReShark partners are working to change that story.

Dr. Erin Meyer of the Seattle Aquarium first discussed the idea of an international partnership in 2018. She helped assemble and lead a group of founding members that has grown to include more than 70 organizations in 15 countries—aquariums, local governments, conservation nonprofits and many others.

Professor Charlie D. Heatubun, head of the Raja Ampat Research and Innovation Agency and the namesake of baby shark Charlie, calls ReShark’s success “proof of the tight collaboration between all the parties.”

Aquariums offer expertise—and eggs

ReShark’s innovative model begins at aquariums.

The eggs that hatched into Charlie and Kathlyn were laid at the SEA LiFE Sydney Aquarium in Australia. They were then transported to Raja Ampat. Charlie and Kathlyn hatched at a special nursery built and managed by the Raja Ampat Research and Conservation Centre located at Papua Diving’s Sorido Bay Resort.

There, the siblings were cared for by a local team of aquarists who proudly consider themselves “shark nannies.” After growing into healthy pups, they’d been brought to marine-protected waters for release.

Charlie and Kathlyn’s journey from an aquarium to marine-protected waters will be repeated many times over. ReShark’s plan is to release 500 baby Indo-Pacific leopard sharks over the next several years.

“If we do what we’re planning to do … within 10 to 20 years, we see them coming back to an absolutely healthy, genetically diverse population with zero chance of extinction,” says Dr. Mark Erdmann of Conservation International and a ReShark founding partner.

“We have species disappearing off the face of this planet at a rapid rate, and in some cases the only place we have the genetics left or we have the species left are often in aquariums.”

Jennifer Hayes, photographer for the National Geographic story speaking on Good Morning America

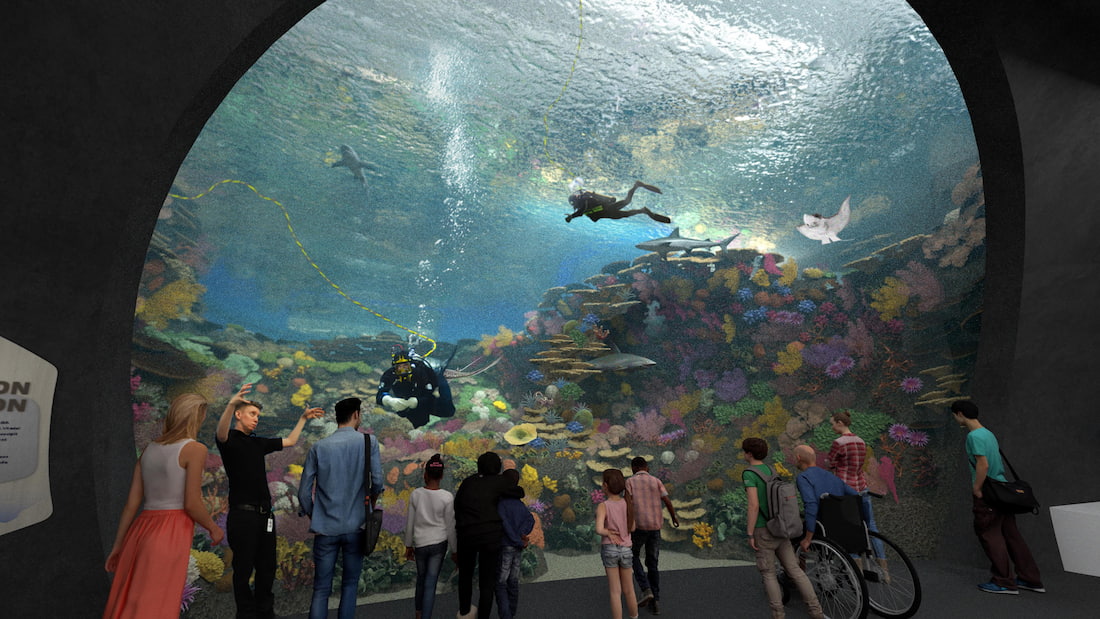

ReShark and the Ocean Pavilion

When our new Ocean Pavilion opens, it will be home to a small number of Indo-Pacific leopard sharks. As a result, we’ll not only continue to play a leadership role in ReShark’s growth—we’ll also be able to directly breed these sharks and send their offspring to Raja Ampat for release. And visitors to the Ocean Pavilion will see these exceptional animals, understand what we’re at risk of losing and learn how they can help.