This story is part of our Nerdy Science Series—how we’re using research and technology in service of a healthy ocean.

Sharks have roamed the ocean since before dinosaurs walked the earth. But today, around a third of the world’s 500+ shark species are threatened with extinction. New research co-authored by Riley Pollom of the Seattle Aquarium offers a way forward.

Why are sharks going extinct?

In a word: overfishing. Fishing—legal and illegal—kills around 100 million sharks every year. Sharks are targeted as sources of food and products; they’re also caught as bycatch in the hunt for other species. Because sharks take longer on average than other ocean animals to mature and reproduce, their populations often don’t recover quickly. Sometimes they don’t come back at all.

When shark species go extinct, the loss has a ripple effect. Ocean food webs are delicate, and the disappearance of a major predator can wreak havoc, sometimes causing the populations of other animals in the system to swell or shrink in unpredictable ways. The impact of these big changes often falls on coastal communities who rely on small-scale fishing for food and income. But as we lose species at an unprecedented rate, all of us will be affected.

Aquariums have the knowledge and capacity to play an important role in population management when things get dire. There’s a point of no return, and we need to avoid it.

Riley Pollom, species recovery program manager, Seattle Aquarium

A clue on how to turn the tide

A team of researchers that included Riley analyzed shark populations throughout the Western Atlantic Ocean over decades.

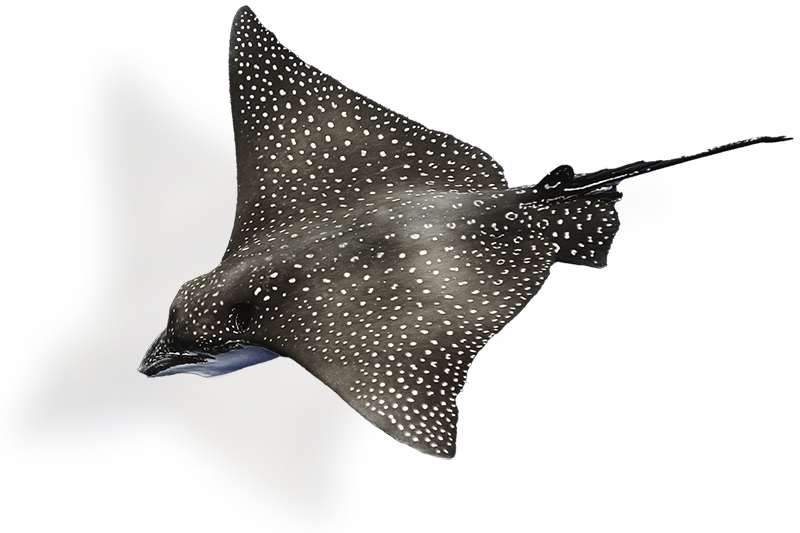

The team’s newest paper, “Conservation successes and challenges for wide-ranging sharks and rays,” focuses on 26 wide-ranging coastal sharks and rays in the Western Atlantic. All are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. For decades, the Western Atlantic has faced a heavy demand for fishing. And sharks there have suffered, often as bycatch in the industry.

But—as the research team found—sharks in the Northwest and Western Central Atlantic are now making a comeback. In fact, some species that were on the verge of collapse in the 1980s and 1990s are now at stable or even growing populations.

Meanwhile, the situation is very different in the Southwest Atlantic. There, almost all populations of shark species—including many of the same species that are recovering in other regions—are still in trouble.

What’s fueled the difference? The answer, researchers found, is strong fisheries management.

Fisheries management refers to setting, enforcing and monitoring strict limits on how many animals can be caught, where and when they can be caught, and other important rules. Where these practices are robust, like the Northwest and Western Central Atlantic, shark and ray populations are rebounding. Where they are weak or nonexistent, many species are on the verge of extinction or heading that way.

“If strong fisheries management measures are implemented elsewhere, we would expect to see similar recovery,” Riley says.

Avoiding the extinction vortex

As the new research shows, protective measures work. But in some cases, those measures aren’t enough.

In a situation that conservationists call the “extinction vortex,” the population of an endangered species drops so low that even if other threats are removed, the species will not recover and may still go extinct. That’s because when populations are small enough, males and females have trouble finding each other. Those that do risk inbreeding, introducing genetic defects and weakening fitness.

In some cases, direct intervention by people might be the only way to avoid the extinction vortex. Increasingly, aquariums are getting involved in this work.

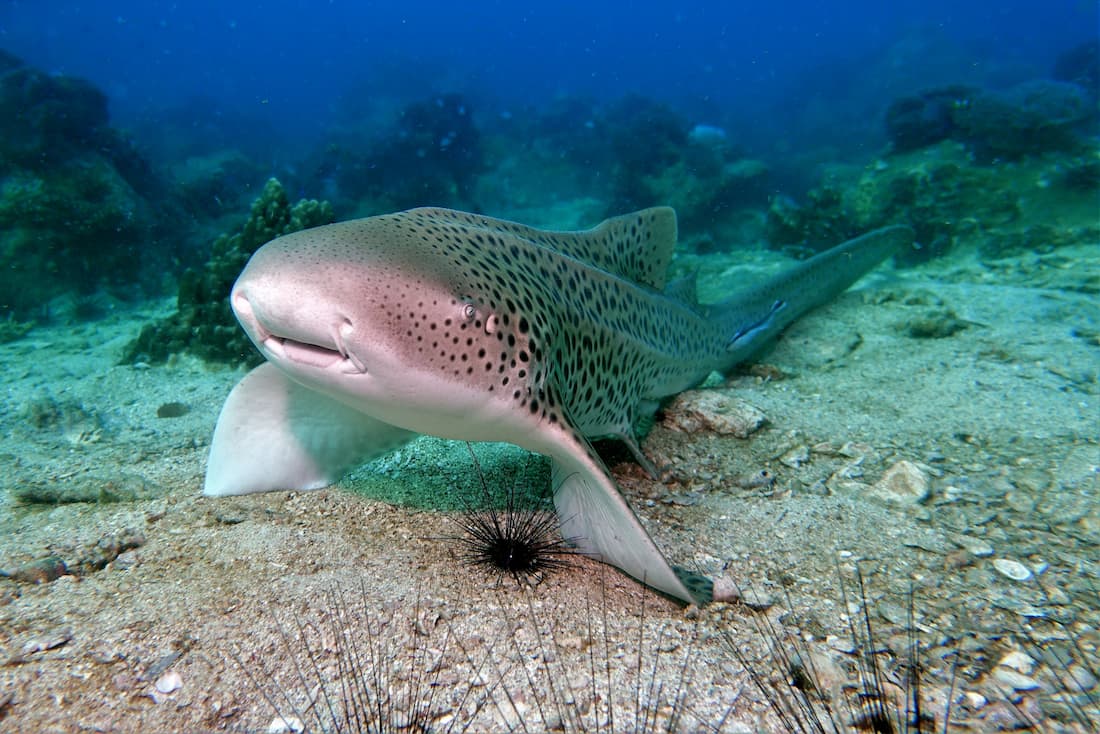

In 2020, the Seattle Aquarium helped launch ReShark—a global collective to recover threatened shark and ray species. ReShark’s first project is to breed and release Indo-Pacific leopard sharks, which have all but vanished from their home waters off the coast of Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Projects like this are still novel for aquariums—but so far, ReShark has had early success rearing shark eggs born in aquariums for release into their marine-protected home waters. (Read National Geographic’s coverage.)

As species recovery program manager, Riley is helping to lead the Aquarium’s growing programs and partnerships to bring back threatened species in Washington State and internationally.

What can individuals do?

Wherever you live, “Vote with the ocean in mind,” Riley says. “Learn and understand politicians’ stances on ocean policies and fisheries management policies.” When we’re informed, we can advocate for setting and enforcing strong fisheries management. Join the Aquarium’s email list to receive alerts on how you can support our state and federal advocacy on behalf of the ocean.