This story is part of our Nerdy Science Series—how we’re using research and technology in service of a healthy ocean.

During 2014, a mass of warm water nicknamed “the blob” simmered and spread in the Pacific Ocean. It lingered until early 2016, wreaking havoc on marine ecosystems and causing a mass coral bleaching event in Hawaiʻi’. Then in 2019, another marine heat wave struck Hawaiʻi, reminiscent of the blob. Smaller heatwaves have followed.

Seattle Aquarium research technician Amy Olsen was born and raised on Hawaiʻi’s Big Island. Rising ocean temperatures, which most scientists attribute to climate change, are transforming her home. Today, as a marine scientist for the Aquarium, Amy is leading scientific papers that analyze how those changes are affecting fish populations off the Big Island’s coast.

"By 2025, marine heatwaves are likely to occur every year. There is an urgent need to see what’s happening now and how we can anticipate and mitigate those changes."

Amy Olsen, research technician, Seattle Aquarium

Working Far Beyond our Walls

For nearly 40 years, Hawaiʻi ecosystems have been part of the Seattle Aquarium experience. If you’ve visited the Aquarium, you’ve likely marveled at Pacific Coral Reef, a lush community of corals, puffers, tangs, wrasses and other members of tropical reefs.

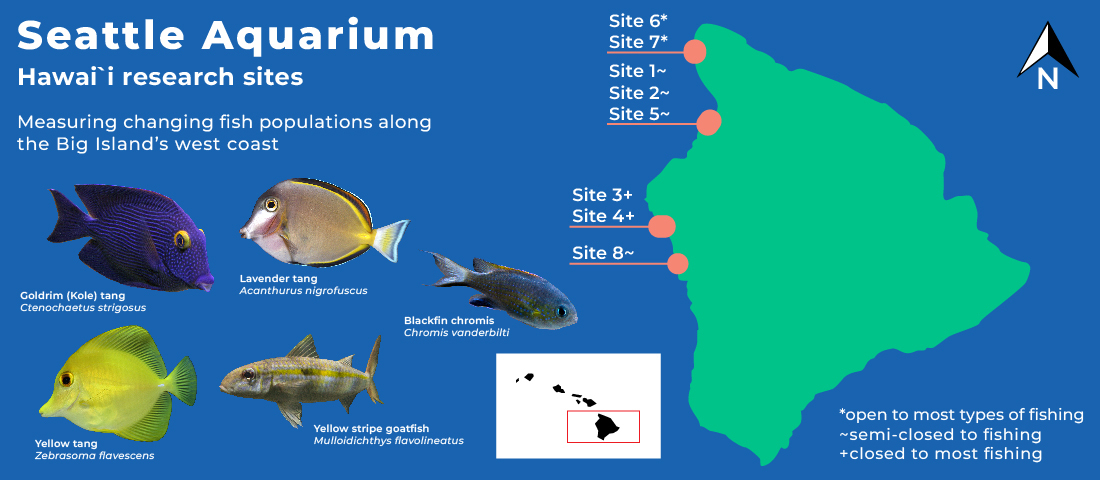

But what isn’t visible to Aquarium visitors is the scientific research that takes place outside its walls. Since 2009, Aquarium researchers have traveled to Hawaiʻi and donned scuba gear to track fish populations in eight locations off the west coast of the Big Island.

Their goal: to provide long-term data on the health of fish populations.

Connecting Research and Home

“This research is a way to give back to the place where I was raised,” Amy says.

She joined the Aquarium’s Hawaiʻi research team in 2014, the same year the blob struck. She later decided to focus her master’s thesis on how marine heat waves affected groups of fish, using Aquarium data gathered between 2009 and 2019.

Amy works closely with Dr. Shawn Larson, senior conservation research manager—who launched the Aquarium’s Hawaiʻi research—and a multidisciplinary Aquarium team that includes conservation researchers, dive experts and scientists who specialize in fish and invertebrates.

The team uses a unique method to measure fish populations each year. It’s the same method we’ve used to monitor local Salish Sea fish populations for decades. Researchers dive along defined 100-meter sections (transects) of the ocean while wearing underwater cameras. As they swim along a transect, they speak into a microphone, narrating the species and number of fish in their line of sight and creating a recording that can be analyzed later. The team uses GPS coordinates and visual notes to return to the same spots year after year without leaving behind physical markers that could impact marine life.

This method proved so efficient in the Aquarium’s Hawaiʻi research—where divers often had more than 100 species in sight—that the team published a special methods paper to share it with other researchers.

Troubled Findings and a Call to Action

Amy’s thesis—published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series last year—analyzed changes in different subgroups of fish following the heatwaves.

The groups included predators, “secondary consumers” (typically small fish that eat other fish or plants), planktivores (animals that eat plankton), corallivores (animals that eat coral), browsers (which eat algae), grazers (which eat short, fibrous turf algae) and scrapers (which effectively clear algae from corals). Why so many groups? Each plays a unique role in their delicate food web.

The research showed that after the 2014–2015 heat wave, fish populations in all groups increased. The group that grew the most were the grazers, tiny fish that eat turf algae.

“One hypothesis is that the heat wave encouraged more algae to grow,” Amy explains. “Fish that graze on it did well because they had more food.”

But any change to ocean food webs is complex. The same warming events that benefitted fish are devastating coral. The breakdown of coral will mean less food for the creatures that eat coral and fewer hiding spots for larger fish. The bottom line: Pulling a thread in ocean food webs can unravel the entire sweater.

My goal is that our scientific partners use this research to inform decision-making and policy. For individuals, I hope it encourages curiosity, behavior change and hope—because our actions do make a difference.

Amy Olsen, research technician, Seattle Aquarium

What can individuals do to help slow marine heatwaves and protect reefs?

A lot, Amy says. One simple action is to use reef-safe sunscreen, whether we’re swimming in Pacific Northwest or tropical waters. Coral reefs exist in both. With this small step, we can do less harm to wild populations of coral, which are already stressed.

Climate change remains one of the biggest challenges we and the ocean face. Shifting our day-to-day habits—from how much we drive to what we eat—matters. So does large-scale policy change. The Aquarium advocates for policies that address climate change and protect our ocean. Get involved by learning more and signing up for Seattle Aquarium action alerts.