If you look at a typical globe or world map, you’ll see many named bodies of water—oceans, seas, gulfs, bays and more. All appear to be distinct. But what actually separates these waters? There are no physical borders or barriers between them. In reality, they’re all connected, flowing together into one world ocean that sustains us all.

A different way of looking at the global ocean

In 1942, South African-American geophysicist and oceanographer Dr. Athelstan F. Spilhaus developed a seawater-focused map of Earth, centered on Antarctica. It was groundbreaking then and is still a vital tool today, providing a way for us to view the world ocean as it is: a single, vast, contiguous body of water. This one ocean connects everything—from the Salish Sea here at home to the faraway reaches of the Coral Triangle and all the waters in between. (Visit us at the Seattle Aquarium to see a wall-sized version of the map near our touch pools!)

Salish Sea, Puget Sound…what’s the difference?

If you live in the Pacific Northwest, you may hear those two terms used interchangeably, as if Puget Sound and the Salish Sea are one and the same. As it turns out, that’s not quite right: Puget Sound is one component of the larger, inland Salish Sea.

What’s an inland sea? The simple definition is a large body of water that’s largely or completely surrounded by land; any connection to the ocean is limited to one or few relatively narrow passages. Two examples you may be familiar with are Hudson Bay in Canada and the Baltic Sea in Europe.

Closer to home, the Salish Sea begins as waters from the Pacific Ocean flow in and out through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, north through the Strait of Georgia in British Columbia and south into and out of Puget Sound. The Salish Sea’s total surface area is about 7,000 square miles.

The Coral Triangle: a reef ecosystem like no other on Earth

On the other side of the ocean is the Coral Triangle, a region of the Indo-Pacific that’s so rich in marine biodiversity, it’s been called the Amazon of the ocean. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) describes it as “the most diverse and biologically complex marine ecosystem on the planet.”

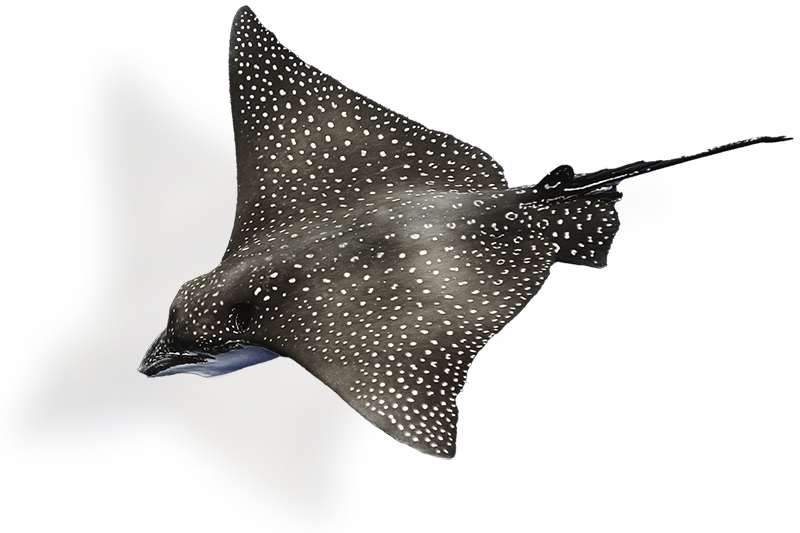

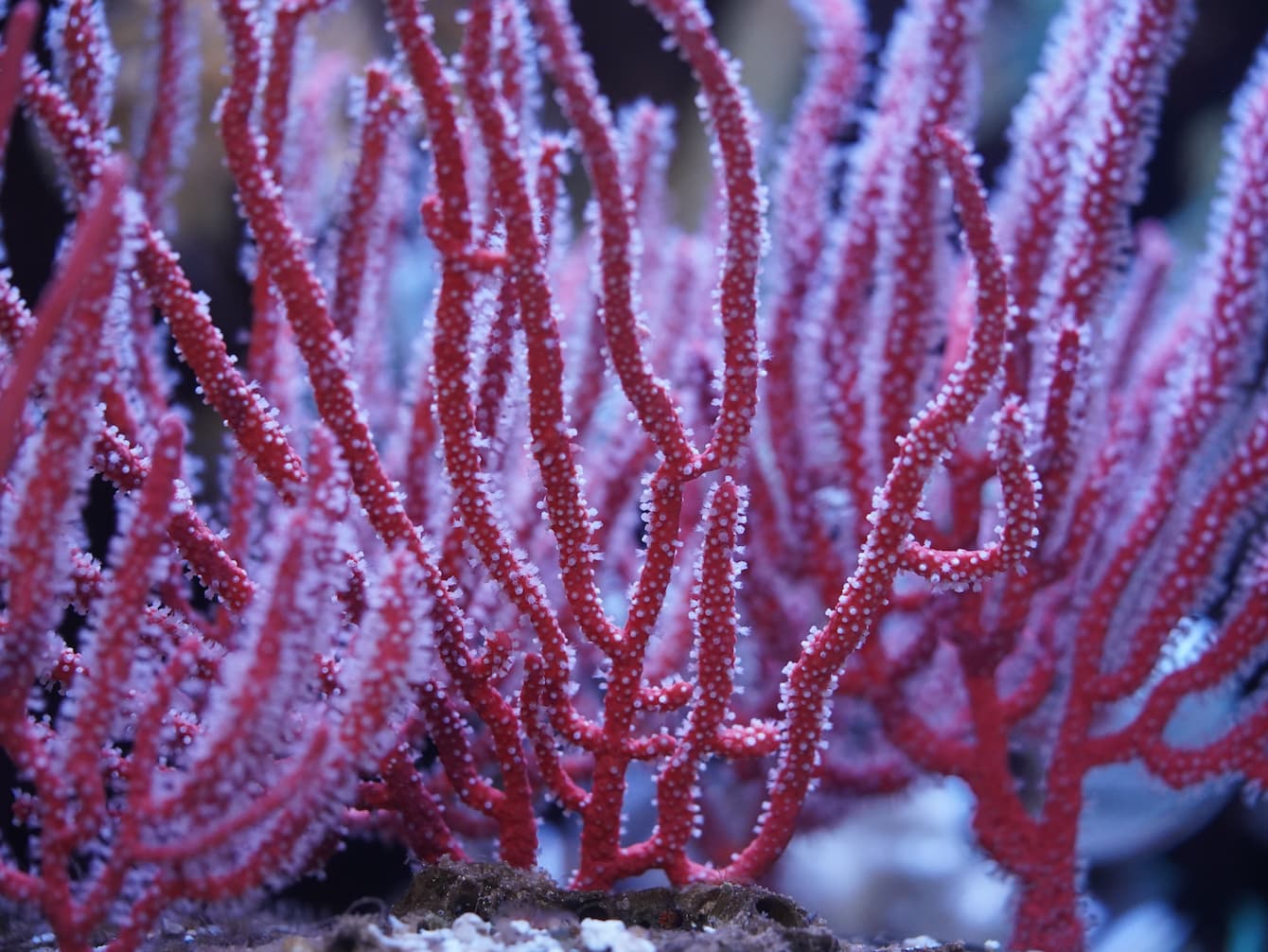

The Coral Triangle is home to more than 600 reef-building coral species and over 3,000 species of reef fish—and that’s just for starters. Its tropical waters flow around parts of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Timor Leste. And, with a surface area of 2.3 million square miles, it dwarfs the Salish Sea (it’s nearly 330 times larger!).

Coral Triangle and Salish Sea: more in common than meets the eye

Despite their differences—size, water temperature and more—these two bodies of water share more characteristics than you might think. For instance, the Coral Triangle is rich in its namesake coral. But did you know that the chilly waters of the Salish Sea are also home to a variety of coral species? And that coral is vitally important to the health of both ecosystems? It provides habitat, spawning, nursery and feeding grounds for a multitude of marine species.

The Coral Triangle is also known for its sharks: whale sharks (the world’s largest fish!), blacktip and whitetip reef sharks, hammerhead sharks and more. Sharks are found in the depths of the Salish Sea as well, including sixgill sharks (one of the top 10 largest predatory sharks in the world) and dogfish—which, despite their names, are sharks! Like corals, sharks are critically important to ecosystem health, whether they’re found in tropical or temperate waters. Why? For one thing, they help keep the ecosystem in balance by regulating populations of their prey.

There’s more: Marine plants provide key habitat in both the Coral Triangle and the Salish Sea. Mangroves live in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including the Coral Triangle. These amazing and highly adaptive trees thrive where most plants can’t: in hot, salty, muddy water. Their roots, below the surface, shelter young fish and offer a place to hide from predators. Here at home, kelp forests serve a similar purpose, providing habitat and protection for a variety of species. And both mangroves and kelp forests sequester carbon, which helps reduce the impacts of climate change.

Shared waters, shared challenges

The common ground isn’t all good news, though. Species native to both the Salish Sea and the Coral Triangle are endangered. For instance, the population of the only abalone species found in Washington waters, xʷč’iłqs (the Lushootseed word for pinto abalone), declined by 97% between 1992 and 2017, with overharvesting as a primary factor. These marine snails, which help maintain the health of kelp forest and rocky reef habitats, are listed as endangered in Washington state.

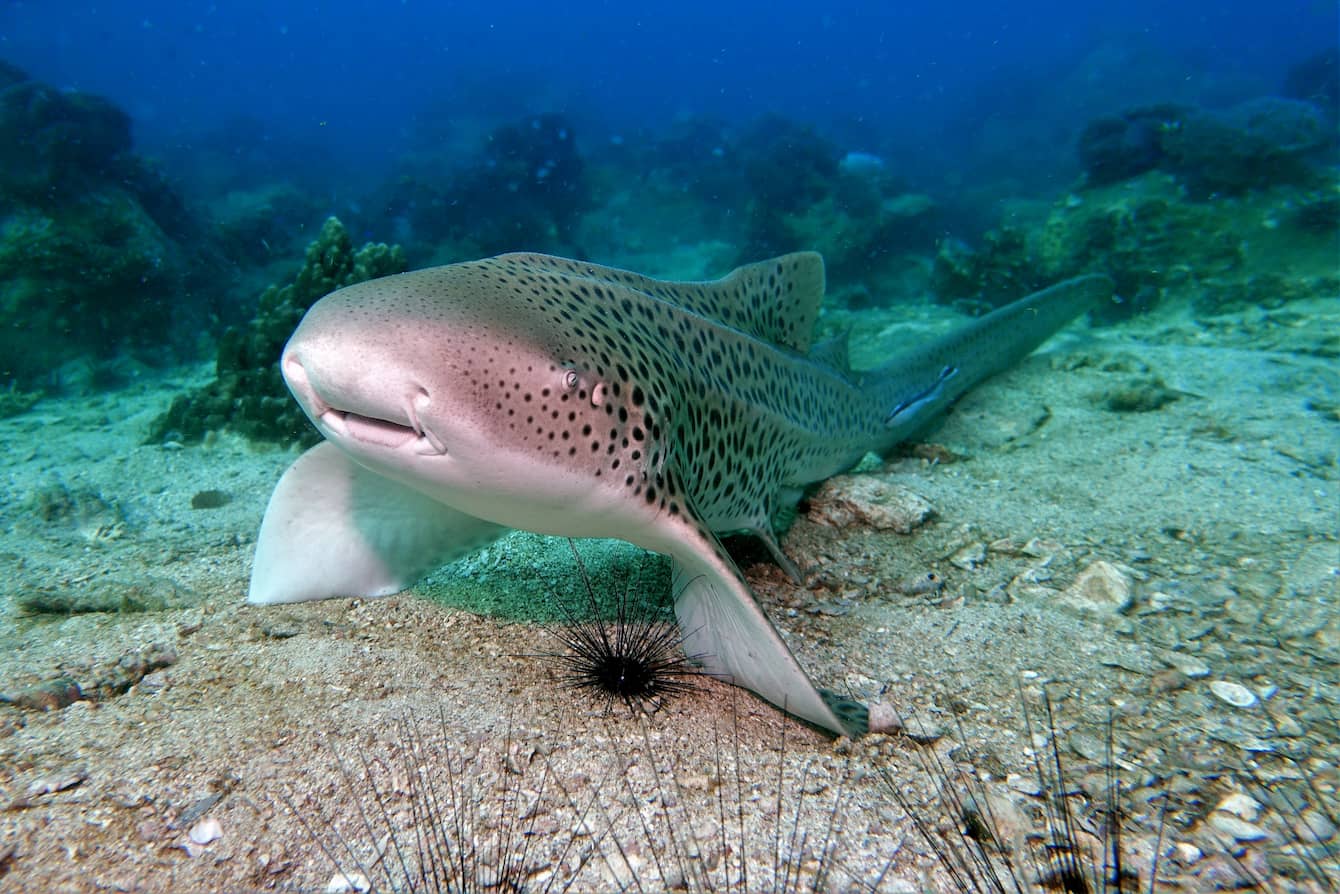

Indo-Pacific leopard sharks (also called zebra sharks, hiu belimbing and other names) in the Coral Triangle are now nearly extinct due to overfishing and habitat loss. Like all sharks, they help maintain a healthy food web and are essential to the wellbeing of their entire ecosystem. (Here’s common ground of a more optimistic kind: the Seattle Aquarium is partnering to help restore both of these species.)

Connected waters also mean connected problems: What happens here impacts waters on the other side of the world and vice versa (read our web story to learn more). Issues like pollution, microplastics and climate change are damaging the health of all waters in Earth’s one ocean. That’s why it’s important to act to protect ocean health. Visit our Act for the Ocean webpage to learn how you can help!