- Fish

Tangs & unicornfish

We are family

Tangs and unicornfish belong to different branches of the Acanthuridae family of ray-finned marine fish. The family’s common name, surgeonfish, refers to the scalpel-sharp blades on their caudal peduncle (base of their tails). When threatened, their tails flex into action with the blades at the ready for self-defense. The family shares many traits—and some peculiar differences.

At the Aquarium

- The Reef, Ocean Pavilion

Home is where the algae is

Tangs, unicornfish and their surgeonfish cousins are found in warm, tropical waters all around the world. They’re drawn to coral reefs for the algae, marine plants and zooplankton that are always on the menu. Feeding mostly in schools helps tangs and unicornfish hold their ground with aggressive defenders of algae beds. With small mouths and tiny teeth, they graze the reef without harming the corals.

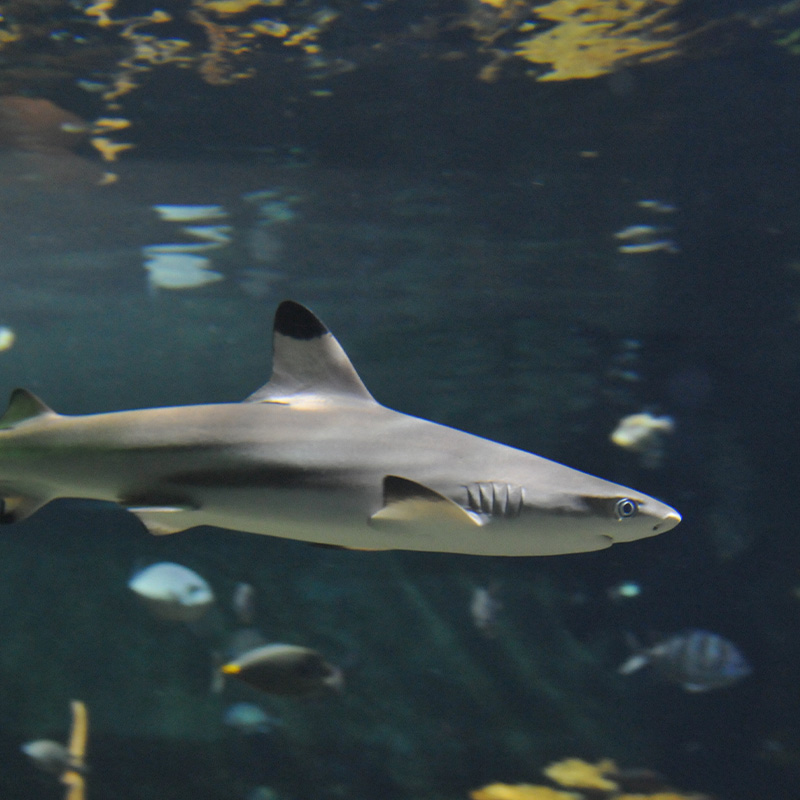

Cousins of many colors

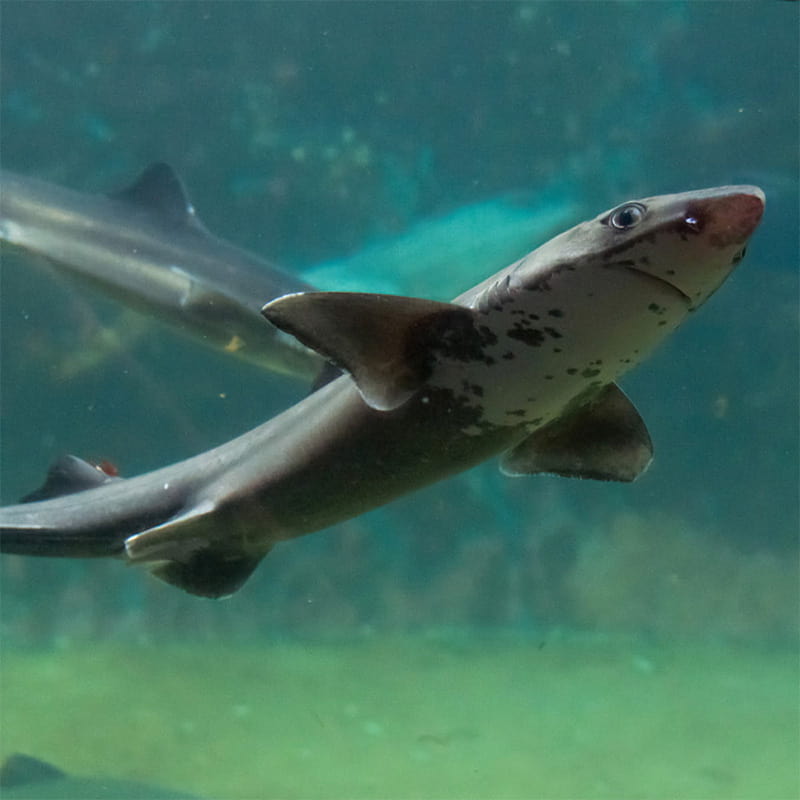

Tangs and unicornfish have oval-shaped profiles, narrow bodies, and eyes set high on their heads. Colors and patterns range from the brilliant, single-hued yellow tangs, Zebrasoma flavescens, to the pale greens and blues of the bluespine unicornfish, Naso unicornis, plus myriad combos and patterns. Most surgeonfish grow from 6 to 15.5 inches—but at 39 inches, the whitemargin unicornfish, Naso annulatus, is the largest of the family. All have the scalpel-like blades, but only unicornfish have a horn between their eyes.

Clues to who’s who

Like most surgeonfish, tangs have one retractable blade on each side and a slot to store it in, but unicornfish have double blades that stay in place. You might expect the horn alone would identify unicornfish, but those horns can be short, long, rounded, pointed or bulbous depending on species. And, some unicornfish do not have horns at all. It’s true!

Fish fertility festival

It takes a village for tangs and unicornfish to ensure the next generation. Through a process of external fertilization, females and males gather in large groups to release eggs and sperm into the sea and, boom! Fertilized eggs. With that, the parents’ work is done—and then things get tough. The tiny, larval hatchlings drift in the current with plankton (and the animals that feed on it) until they grow enough (and are lucky enough) to find shelter in a reef.

Progress on populations

Climate change, pollution and development continue to damage marine habitats, but there are signs of hope. For example, yellow tang populations were being depleted before marine protected areas were established. Now tangs for home aquariums are bred in human care, leaving more wild tangs to thrive in the wild. Tangs, along with unicornfish, are currently listed as species of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. You can make a difference for these fish, no matter how far you live from the tropical Pacific. Learn how by visiting our Act for the ocean webpage.

Quick facts

With small mouths and tiny teeth, tangs and unicornfish graze the reef without harming the corals.

In the Acanthuridae family, only unicornfish have horns, but some unicornfish have no horns at all.

Unicornfish eat macro algae that would otherwise smother corals, and kindly leave their poop to feed corals.